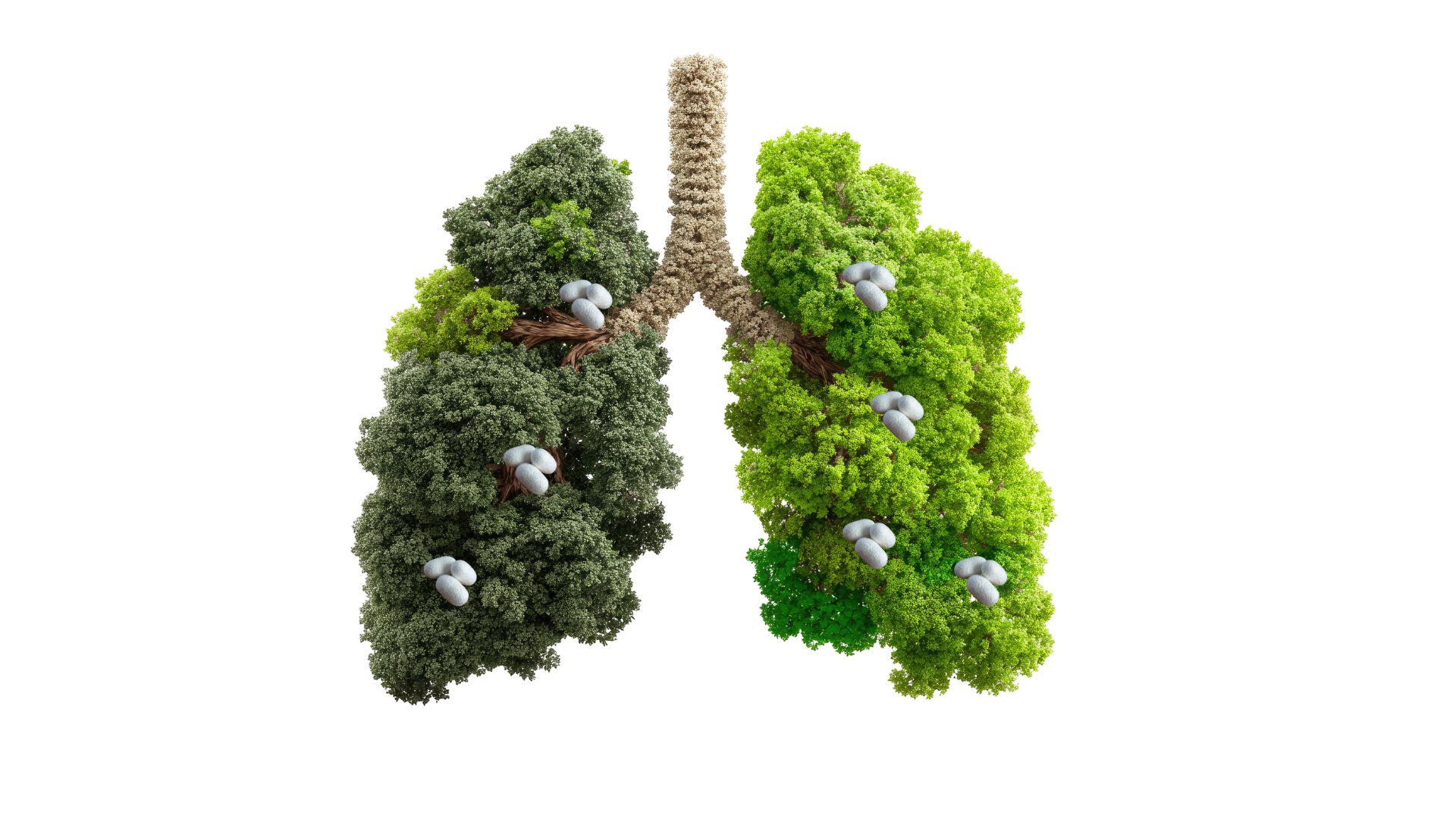

Among the properties that make sericin so interesting are its film-forming ability, namely the capacity to create thin and continuous films on biological surfaces, its hydrophilic nature, which facilitates interaction with aqueous environments and moist tissues, and its well-documented antimicrobial activities that extend to a broad spectrum of pathogens. Particularly promising is the application of this protein in the field of respiratory health, an area of research that is rapidly expanding, especially in light of the growing interest in innovative preventive and therapeutic strategies in the context of pulmonary infections—a phenomenon made even more urgent by recent pandemics and the increasing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

The respiratory system, constantly exposed to a myriad of potentially harmful agents through the air we breathe, requires protective systems that are both effective and well tolerated. Sericin, with its favorable safety profile and its multiple biological functions, could represent a natural and sustainable response to this need, positioning itself as an innovative frontier in the protection of respiratory mucosa and in the management of pulmonary infections.

Biochemical structure and functional properties

Sericin is distinguished by a peculiar amino acid composition, characterized by an extraordinary abundance of polar amino acid residues, in particular serine, which can constitute up to 30% of the protein sequence, threonine, and aspartic acid, together with significant amounts of glycine and other hydrophilic amino acids. This particular molecular architecture is not random but reflects the functional evolution of the protein within the context of the silk cocoon, where sericin plays the role of a natural “glue” that holds together fibroin filaments, the main structural component of silk.

The hydrophilic properties deriving from this composition confer on sericin a high capacity to bind water molecules, creating a hydrated microenvironment around itself that is fundamental for its biological functions. This characteristic translates into the ability to form continuous protective films when applied to biological surfaces—films that maintain an optimal balance between selective permeability and physical protection. The three-dimensional structure of sericin, characterized by regions of random coil alternating with segments of secondary organization, allows it to conformationally adapt to the surfaces with which it interacts, maximizing adhesion and protective efficacy.

From a functional point of view, sericin exhibits an impressive range of biological activities that go well beyond its purely physical properties. Its antioxidant activity, widely documented in the literature, derives from the presence of functional groups capable of neutralizing reactive oxygen species and free radicals, phenomena that are particularly relevant in the inflammatory processes accompanying respiratory infections. Serine and threonine residues, with their hydroxyl groups, can act as electron donors, while aromatic amino acids, although present in smaller amounts, contribute to the ability to absorb and dissipate the energy associated with reactive species.

The antibacterial activity of this protein represents another aspect of great interest and is attributable to multiple mechanisms, including the alteration of bacterial membrane integrity, interference with essential metabolic processes, and the ability to chelate metal ions required for microbial growth. Studies have shown that sericin can impair the formation of bacterial biofilms, complex structures that represent one of the main causes of resistance to conventional antibiotics and of the chronicization of respiratory infections.

Mucosal protection of the respiratory epithelium

The epithelium of the respiratory tract constitutes an extremely sophisticated and multilevel defense system, representing the first and most critical line of defense against the immense variety of inhaled pathogens, airborne particulate matter, and environmental pollutants that daily threaten the integrity of the respiratory system. This specialized epithelium is composed of different cell types, including ciliated cells, mucus-producing goblet cells, basal stem cells, and resident immune cells, organized in a pseudostratified structure that optimizes barrier functions, mucociliary clearance, and immune response.

Respiratory mucus, produced mainly by goblet cells and submucosal glands, forms a fluid and viscoelastic layer that traps particles, microorganisms, and harmful substances, allowing their elimination through the coordinated movement of cilia. This mucociliary system, however, can be compromised by numerous factors, including viral and bacterial infections, exposure to air pollutants, tobacco smoke, unfavorable environmental conditions such as excessively dry or cold air, and chronic pathological states such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The topical application of sericin on respiratory mucosa can contribute significantly to the protection and maintenance of the functional integrity of this complex system through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The formation of a continuous protective film, determined by the film-forming properties of the protein, creates a semipermeable physical barrier between the potentially hostile external environment and the delicate epithelial surface. This film, while maintaining the permeability necessary for gas exchange and the transport of physiological molecules, significantly reduces epithelial dehydration—a phenomenon particularly critical in dry environments or during oral breathing—and preserves the integrity of the cellular barrier by protecting intercellular junctions, which represent vulnerable points for microbial penetration.

The moisturizing effect of the molecule is particularly relevant considering that proper hydration of mucus is essential to maintain its optimal rheological properties. Excessively dense and dehydrated mucus compromises mucociliary clearance, favoring the stagnation of secretions and bacterial colonization. The ability of sericin to bind and retain water helps maintain the correct hydration balance of the mucosal surface, supporting the functionality of the natural clearance system.

Under inflammatory or infectious conditions, when alterations of mucus and epithelium favor microbial penetration and the worsening of tissue damage, the protective role of sericin becomes even more valuable. During respiratory infections, the epithelium undergoes direct damage caused by pathogens and collateral damage resulting from the host inflammatory response. Infected epithelial cells may undergo programmed cell death, intercellular junctions weaken, increasing paracellular permeability, and mucus composition changes with increased viscosity and reduced antimicrobial properties. In this context, the sericin film can act as a sort of temporary “biological patch,” reducing the exposure of damaged cells to further insults and supporting endogenous repair processes.

Moreover, sericin appears to exert direct effects on the viability and functionality of epithelial cells. In vitro studies have shown that the protein can stimulate cell proliferation and the production of extracellular matrix proteins, processes that are fundamental for tissue repair. Its antioxidant activity protects cells from inflammation-induced oxidative stress, while its anti-inflammatory properties, mediated in part by the modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, help limit tissue damage secondary to an excessive immune response.

Antimicrobial activity and antiviral potential

The antimicrobial properties of silk protein have been the subject of numerous in vitro studies that have progressively outlined a complex picture of the mechanisms of action through which this natural protein exerts inhibitory effects on a wide spectrum of pathogenic microorganisms. The ability to inhibit the growth of both gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, and gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosaand Escherichia coli, suggests mechanisms of action that do not depend exclusively on the structure of the bacterial cell wall but involve more fundamental molecular targets and biological processes.

The antibacterial mechanism appears to operate on multiple fronts. First, sericin can interact electrostatically with the negatively charged bacterial surface, altering membrane integrity and causing the leakage of essential intracellular components. This membranotropic effect is particularly pronounced against bacteria in the active growth phase, when the membrane is more dynamic and vulnerable. In addition, the ability of sericin to chelate metal ions such as iron, zinc, and magnesium—essential cofactors for numerous bacterial enzymes—can compromise fundamental metabolic processes, slowing microbial growth or causing cell death.

More recently, the attention of the scientific community has focused on the antiviral potential of sericin. Preliminary evidence suggests that sericin may interfere with different stages of the viral replicative cycle, from initial attachment to the host cell to the release of new viral particles.

The most studied antiviral mechanism concerns interference with viral adhesion to host cells. Many respiratory viruses, including influenza, coronaviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus, use surface glycoproteins to recognize and bind specific cellular receptors, a process essential for infection. Sericin, with its structure rich in hydrophilic groups and surface charge, could compete for binding to cellular receptors or interact directly with viral proteins, altering their conformation and reducing their affinity for receptors. This mechanism of “competitive inhibition” or “molecular masking” would represent an elegant antiviral strategy that does not require the protective molecule to enter the cell and could be effective against different types of respiratory viruses.

In the specific context of respiratory infections, such a mechanism could have a significant impact by reducing the local viral load in the early stages of infection, a critical moment that often determines disease severity. By limiting infection of epithelial cells in the upper airways, sericin could reduce the progression of infection toward deeper pulmonary districts, where complications can become severe or even fatal. In addition, by reducing the number of infected cells, the production of inflammatory mediators responsible for symptoms and tissue damage associated with respiratory viral infections would also be limited.

Some studies have also suggested that sericin may stimulate innate immune responses in respiratory epithelial cells, increasing the production of interferons and other antiviral cytokines that confer a state of resistance to infection. This immunomodulatory effect would add a further level of protection, complementary to direct antiviral activity, creating a mucosal environment less favorable to viral replication.