While the accumulation of electronic waste continues to represent a global environmental challenge, with millions of tons of obsolete devices ending up in landfills each year, scientific research has begun looking to nature to find innovative solutions that can combine technological functionality with environmental sustainability.

From silk to semiconductors

Fibroin extracted from the cocoon of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, has demonstrated properties that go far beyond traditional textile applications. Studies have revealed that this natural biopolymer can be processed into ultrathin films with excellent dielectric properties, comparable to those of synthetic materials commonly used in the electronics industry. Research published in Advanced Materials in 2010 documented how fibroin can be deposited on substrates in layers of just a few nanometers, while maintaining extraordinary structural uniformity and insulating properties superior to those of silicon dioxide, the industrial standard for dielectrics in conventional chips.

What makes fibroin particularly interesting in this context is its ability to undergo controlled transition from the beta-sheet crystalline structure, which is extremely stable and water-resistant, to the soluble form that can be degraded enzymatically or hydrolytically. This structural duality allows engineers to literally program the longevity of the device by regulating the degree of crystallinity during the manufacturing process. And by varying treatment conditions, such as exposure to water vapor or heat treatment, it is possible to obtain devices that dissolve completely in a few hours or maintain their functionality for months or even years.

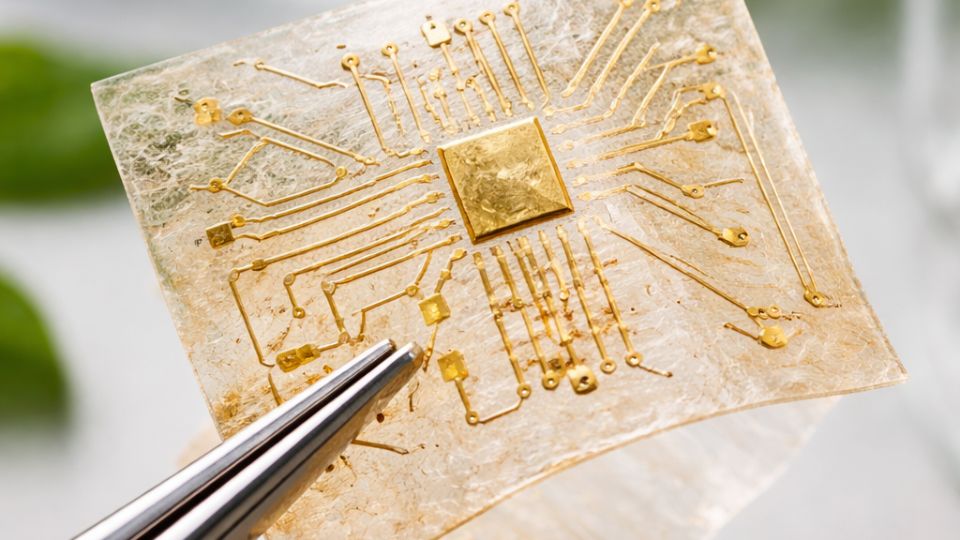

Circuital architectures on protein substrates

The practical realization of functional microchips based on fibroin requires the development of entire technological platforms that integrate this biomaterial with active electronic components. Pioneering studies conducted by John Rogers and collaborators have demonstrated the feasibility of fully functional field-effect transistors built on fibroin substrates. These devices use monocrystalline silicon-based semiconductors, deposited in ultrathin membranes on the protein surface, along with biodegradable metal electrodes such as magnesium and tungsten.

The main challenge in constructing these biological circuits lies in the interface between inorganic semiconductor materials and the organic substrate. Fibroin offers unique advantages in this regard thanks to its chemically modifiable surface, which can be functionalized with specific groups to improve the adhesion of metals and semiconductors. Research published in Nature Materials has highlighted how oxygen plasma treatment of the fibroin surface can create hydroxyl groups that promote uniform deposition of metal oxides, fundamental for constructing high-performance transistors.

A particularly innovative aspect concerns the use of fibroin not only as a passive substrate, but also as an active dielectric layer within the transistors themselves. Fibroin films of controlled thickness, ranging between ten and one hundred nanometers, can effectively function as gate insulators in organic thin-film transistors, showing capacitances comparable to high-performance synthetic dielectrics and reduced leakage current, a critical parameter for the energy efficiency of devices.

Programming temporal degradability

One of the most fascinating characteristics of fibroin-based microchips is the possibility of precisely designing their temporal functionality window. This temporal programming capability is particularly relevant for biomedical applications, where implantable devices must perform specific functions for determined periods before dissolving completely in the organism without leaving toxic residues.

The degradation kinetics of fibroin depend on multiple interconnected factors. The first and most important is the content of crystalline beta-sheet structures, which confer mechanical stability and resistance to hydrolysis. The relationship between the degree of crystallinity and degradation time in physiological solutions has been systematically mapped, demonstrating that samples with crystallinity exceeding seventy percent can remain stable for over a year under simulated bodily conditions, while samples with crystallinity below thirty percent degrade completely within a few weeks.

A second approach to controlling degradability involves modulating the thickness of the fibroin film. It has been demonstrated that degradation speed follows kinetics that are not simply proportional to thickness, but show complex behaviors related to water diffusion through the protein matrix and enzymatic activity. Ultrathin films, on the order of one hundred nanometers, can degrade in a few hours if exposed to specific proteases such as protease XIV, while films of several micrometers require weeks or months for complete degradation.

A third mechanism for controlling degradability emerges from the possibility of incorporating biocompatible crosslinking agents that create additional covalent bonds between fibroin chains. Japanese researchers have developed methodologies based on the use of genipin, a natural crosslinker extracted from the fruit of Gardenia jasminoides, which allows for significantly increasing resistance to enzymatic degradation without compromising the biocompatibility of the material. This approach has enabled extending the functional life of implantable sensors based on fibroin from a few weeks to several months.

Biomedical applications

One of the applications in the biomedical field concerns transient post-operative monitoring systems. After complex surgical interventions, especially in neurological or cardiovascular settings, it would be extremely useful to be able to monitor critical physiological parameters such as temperature, pressure, pH, or concentration of specific metabolites directly at the operative site. Traditionally, this would require the implantation of sensors that then need to be surgically removed, with the risks and costs associated with a second intervention. Fibroin-based devices elegantly solve this problem by spontaneously dissolving once their diagnostic mission is complete.

Another fascinating frontier concerns transient therapeutic systems, particularly for controlled electrical stimulation of nervous and muscular tissues during the healing phase from trauma and surgical interventions. Studies have demonstrated the feasibility of stimulator electrodes based on fibroin and magnesium, capable of delivering therapeutic electrical impulses to accelerate peripheral nerve regeneration after injuries. These devices dissolve completely within eight to ten weeks, exactly the critical period for nerve regeneration, eliminating the need for surgical removal and reducing the risk of long-term complications associated with the presence of permanent foreign bodies.

Particularly innovative is the application of biodegradable microchips for controlled drug release with electronic feedback. In Korea, systems have been developed that integrate drug reservoirs with biochemical sensors and control circuits, all realized on fibroin substrates. These devices can measure in real time the concentration of specific biomarkers and release precise doses of drug in response, implementing adaptive therapeutic schemes that self-regulate based on the patient's physiological conditions. Programmed degradability ensures that, once the therapeutic cycle is complete, no residue remains in the organism.

Conclusions

The convergence between biotechnology, materials science, and electronics represented by fibroin-based biodegradable microchips constitutes an illuminating example of how nature can inspire radically innovative technological solutions. In this regard, the trajectory of research suggests that in the coming years we will witness a substantial expansion of practical applications of these devices, with potentially transformative impacts both in medicine and in the environmental sustainability of the electronics industry.